I had a trip into Berkshire a few months ago and to Childrey, where the church is a complex building of extraordinary interest, with lots of medieval glass and numerous late medieval monumental brasses.

In the south transept, there is a fine early sixteenth-century monument of Purbeck marble which is built up against the north wall, with brasses still in place against the back of the monument. It is in an extraordinary position and cuts into the arch that divides the transept from the nave, but appears to be in its original place. The brasses show two figures: a man and a woman rising from the dead and they stand in their shrouds in two individual tomb chests. From their mouths are scrolls, both invoking the Holy Trinity for the salvation of their souls.

The man’s scroll reads:

‘Libera nos, salva nos, justifica nos, O beata Trinitas’

(Free us, save us, defend us, O blessed Trinity)

While the woman’s reads:

‘Sancta Trinitas unus Deus, misere nobis’

(Holy Trinity one God, have mercy on us).

There are no inscriptions on this monument and it is possible that there never where. The only other identifying markers on the tomb are two shields, but we’ll come back to them in a minute.

As I was photographing this wonderful monument, I noticed that the edge of another brass could be seen appearing from under a carpet. On top of the carpet was placed an electronic piano, two piano stools and a music stand!

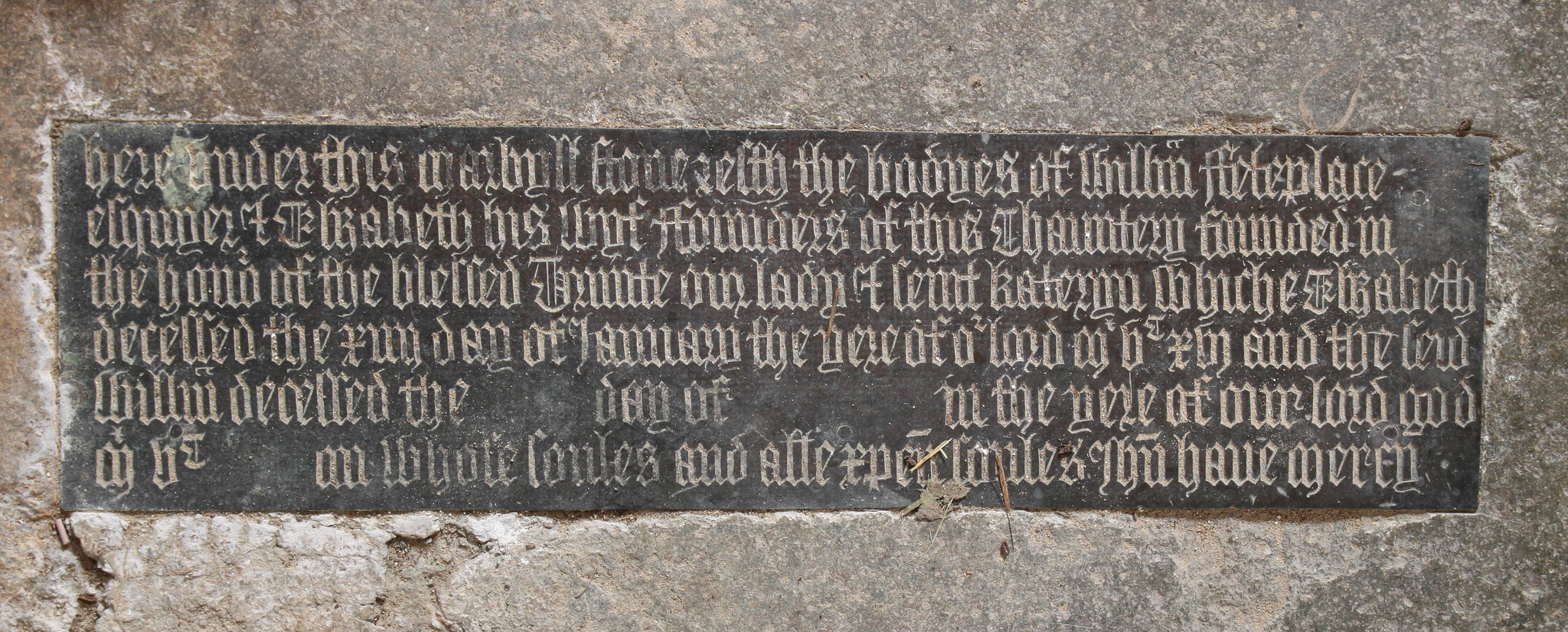

I moved all this away, pulled up the carpet and it revealed another sixteenth-century brass, with an inscription and three shields. The shields on this brass were exactly the same as those on the Purbeck marble tomb, indicating that this was almost certainly a second monument to the same people.

The inscription identifies the people commemorated by these two monuments as William Fettiplace (died 1528) and his wife Elizabeth (died in 1516), who owned the Manor of Rampaynes opposite the church. This was the ancestral seat of her Elizabeth’s family the Walronds and the transept contains monuments both to her Mother and her grandparents, which will the subject of a further post. William and Elizabeth’s brass also has an interesting reference to the foundation of a perpetual chantry by them in the south transept where the tombs remain. It says that William and Elizabeth were:

‘ffounders of this chauntery, founded in the honour of blessed Trinity, our Lady, and sent kateryn’.

The dedication of a chantry in honour of the Trinity in this space would explain why the figures on the Purbeck marble monument, are seen to be invoking the Holy Trinity so directly.

John Nichols the Georgian antiquarian very helpfully includes in his 1783 volume Collections towards a parochial history of Berkshire, a transcript of the deed of foundation for the chantry mentioned in this brass, although he frustratingly doesn’t give an indication of where he had seen this deed. The deed dated to July 1526, two years before William Fettiplace’s death, records his intentions as he sets up this chantry and how he wants it to operate. There’s no reason to doubt this document’s authenticity and it makes for extremely interesting reading, giving detailed instructions on the day to day running of this perpetual chantry, but also fascinating evidence of the ritual function of the surviving monuments.

The deed states, just as the inscription on the brass makes clear, that the chantry was dedicated to the Holy Trinity, Our Lady and St Katherine. A chantry house (which still survives) to the north-east of the church, was provided and a chantry priest and three poor men were to be housed in it. The chantry priest was to assist the parish priest and was to ‘attend in surplice’ when the mass was sung in the parish church on Sundays and holidays and was also to keep a free school in Childrey. He was to celebrate mass at the chantry altar five times in the course of the week and was to receive a stipend of £8 per annum, out of which he was to support himself and also pay for the vessels, vestments, lights, and everything else that was necessary for the mass. The three poor men were to be in attendance at mass and were to receive 9 pence a week for food and also annual payments of 3 shillings & 4 pence for a gown and 2 shillings and 8 pence for firewood.

In the chantry were to be what are referred to as two ‘tables’, one written in English and one in Latin. The English ‘table’ was to state the names of those for whom the priest and poor men were to pray. The second table in Latin was an altarpiece and it was to stand on the altar of St Katherine, which was presumably the primary altar in this space below the transept’s east window. This altarpiece also recorded the names of the benefactors and it was also to contain the following imagery:

‘In the middle of this table is a crucifix, and around it the pictures of the living and the dead aforesaid, upon their knees before it’

This was to be renewed, presumably repainted, from time to time at the cost of the chantry priest. The purpose of the painted altarpiece is made explicitly clear:

‘It was to stand upon the altar of St Katherine before the chaplain and his successors, that they may have spiritual remembrance of the living and the dead before mentioned ‘in secretis missarum suarum”

This altarpiece with its inscription and donor images, was a visual aid for the benefit of the priest celebrating mass so that when he got to the commemoration of the living and departed in the Canon of the mass, he would remember William and Elizabeth Fettiplace and their families.

It gets even more interesting, in this deed it is made clear that the Purbeck tomb of William and Elizabeth Fettiplace was erected by William before he died and that it was to have a significant ritual purpose. It states that after every mass of Requiem celebrated at the altar the priest:

‘turning himself to the [the founder’s] tomb, shall openly and aloud say De profundis with the accustomed prayers and suffrages, rehearsing the names of those for whom the said mass is celebrated’.

Turning to the tomb implies that Psalm 129 was said facing the Purbeck marble tomb as the priest gazed at the shrouded images of the Fettiplace’s rising from their graves.

There was a ritual role for the poor men of the chantry, which was also focused on the tomb. At the end of mass, they were to gather at the tomb and the senior man was to say ‘publically and openly’ in English:

‘For William Fetyplace’s soule, and the souls of Elizabeth his wife, ther fathers and mothers, brethrens and sisters, ther friends, benefactors, and for all the soules that we be bounde to pray for’

They were then to kneel before the tomb and recite the Lord’s Prayer and the Ave Maria and then they were to make:

‘with their hands the sign of the cross upon the ground; and afterwards … devoutly kiss the same’

This sort of evidence that provides a deep insight into the way a late medieval chantry worked and the relationship between objects and ritual is rare. William Fettiplace had strong personal ideas, borne out of a deep inculturation in late medieval Catholic piety, that directed how he would bring about his own memorialisation in perpetuity. Both the liturgy and subsidiary ritual and the monuments and ‘tables’, were designed to interact with one another and so create indelible patterns of memorialisation that would benefit Fettiplace’s soul. Of course, Fettiplace’s perpetual provision was of short duration, the dissolution of the chantries saw the liturgy, ritual, altar and the painted ‘tables’ removed within less than twenty years of his death, leaving only the two monuments behind. I suppose you could say that without the associated liturgical and ritual action taking place before and in proximity to them, the monuments are in a sense incomplete.

Bibliography

J. Nichols, Collections Towards a Parochial History of Berkshire (London, 1783), pp. 66-80.

‘Parishes: Childrey’, in A History of the County of Berkshire: Volume 4, ed. William Page and P H Ditchfield (London, 1924), pp. 272-279. British History Onlinehttp://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/berks/vol4/pp272-279 [accessed 10 October 2018].

Profoundly interesting. Do you think the priest would have been able to supplement his £8 pa by doing other jobs? Can we assume that other contemporaneous chantries ran along similar lines? (Childrey is historically in Berks, but in Oxfordshire for administrative purposes now.)

LikeLike

No the deed is clear that the chanter couldn’t hold another living. Having said that £8 in 1526 was an extremely good living for a priest and lot of beneficed clergy could not expect to receive that. I’m sure a lot of chantries operated similarly too, but evidence is scanty. In forthcoming article I talk about another in Norfolk, where one of the chantry priests was Rector of two livings. Regarding county boundaries, I’m afraid I ignore the post 1974 boundaries in anything I write about the past. Childrey was in Berkshire when the chantry was founded and Pevsner includes it in the Berkshire volume of the Buildings of England.

LikeLike

Thanks again. I wonder how dutifully chantry priests carried out their roles, especially years after the deaths being commemorated. I agree that Childrey ‘is’ in Berks, though not everyone, especially younger people, are aware of this so it’s probably convenient to mention in passing the boundary change.

LikeLike

I don’t know, I don’t think there has been a systematic study of chantries in quite the way the monasteries have been studied. I was born in 1977 after the boundary changes and have always used the historic county boundaries as a matter of course, following the Professor Pevsner’s lead. I don’t think I could bring myself to change now.

LikeLike

I entirely agree that when writing historically the traditional county boundaries are the ones to use (if only because it makes it easier to look things up in Pevsner and many other reference books). The inhabitants of Childrey when the chantry was established would have thought of themselves as living in Berks. But it does no harm to acknowledge that some boundaries have changed for modern administrative purposes.

LikeLike

That is a place which is on my list to visit now I want to visit the church sooner. Hope you dont mind me pointing out that it is in Oxfordshire, it used to be in Berkshire.

LikeLike

It is well worth it, a tremendous amount to see and take in. Yes it’s in modern Oxfordshire, but for all historical writing I use the historic county boundaries as does the Buildings of England series.

LikeLike